America’s Community Colleges: Time to Step Up

October 15, 2020

At a Glance

In this op-ed, Robert Schwartz of the Harvard Graduate School of Education and JFF, challenges community colleges to step up and address the major crises of our time—and shares recommendations on how they can do so from a recent report.

In this op-ed Robert Schwartz, of the Harvard Graduate School of Education and JFF, challenges community colleges to step up and address the major crises of our time—and shares recommendations from a recent report on how they can do so.

The country is facing two major workforce crises—one immediate, the other longer-term—that America’s community and technical colleges are uniquely equipped to address.

The Unemployment Crisis

The first crisis is represented by the 20 million newly unemployed workers, many of whose jobs may not return. We are already seeing evidence that low-wage service workers in the restaurant, hotel, and retail sectors are asking how they might gain the new skills needed to get started in fields like health care and IT where there are good jobs that require something beyond high school but not necessarily a four-year degree.

Only our community colleges have the scale and reach to be able to respond adequately to this problem. Apprenticeships, coding boot camps, and other programs funded through the federal workforce system, as excellent as the best of them are, can only serve a tiny fraction of the students currently being served through the non-credit-bearing division of community colleges, typically called continuing education.

But will community colleges embrace the challenge of meeting this crisis? If so, they will need new or expanded funding streams to support these displaced workers, and new partnerships with both state government and regional employer associations—partnerships that will require bold leadership from the colleges.

The Economic Opportunity Crisis

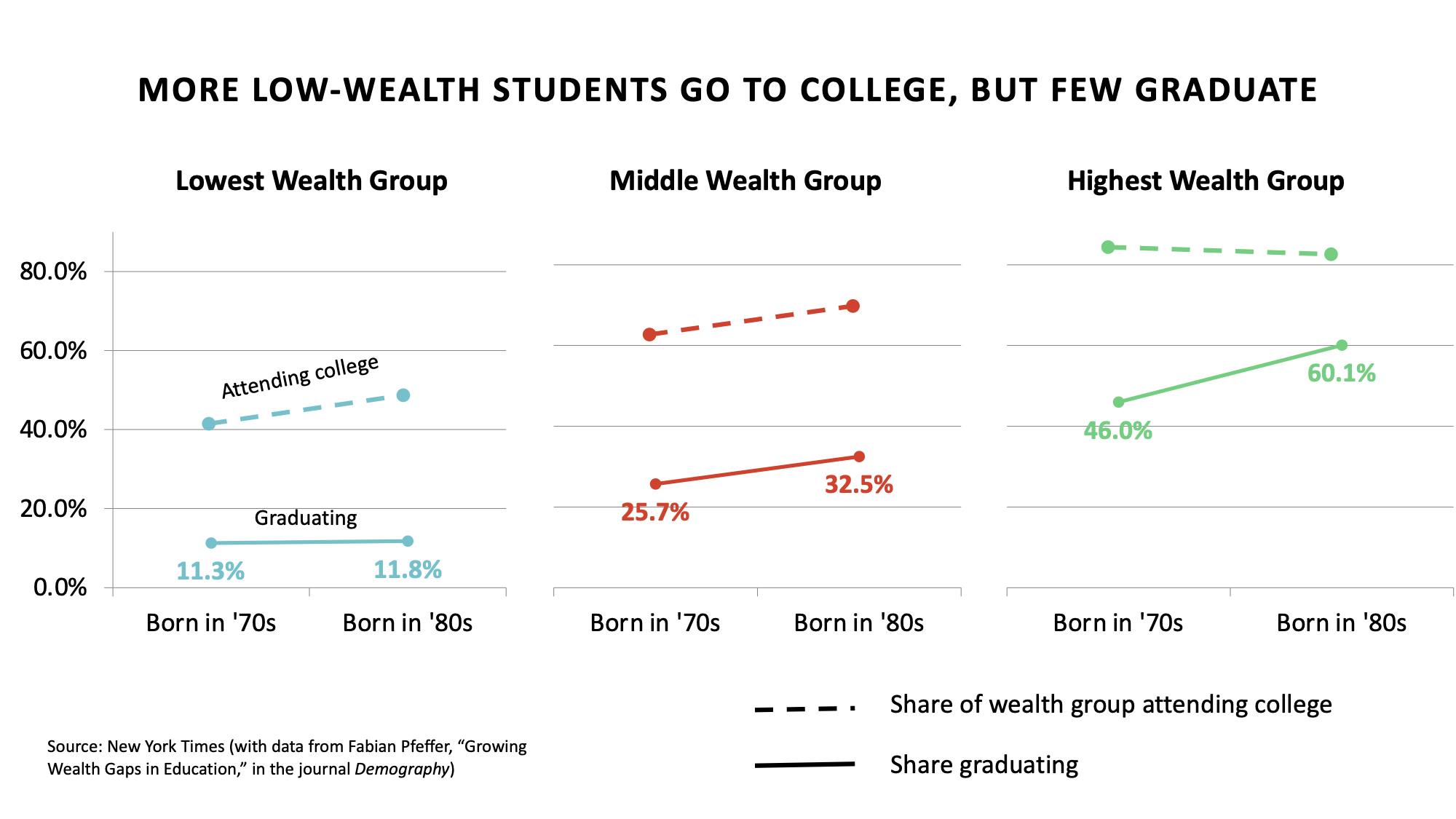

The longer-term crisis is inequitable access to economic opportunity, making mobility out of reach for those who would most benefit from it. The crisis is best understood by looking at the rates of four-year college attainment by age 25 of all young people born in the 1970’s and 80’s and dividing them into three groups by family wealth (see the graph below). While young people born into the high- and middle-wealth groups made steady progress in college attainment over this 20-year period, rising respectively to 60 percent and 33 percent attainment rates, those born into the lowest-wealth group made no progress at all, remaining stuck at under 12 percent.

This suggests that if we are waiting around for four-year higher education institutions to solve the problem of stalled economic and social mobility for young people born into families with low levels of wealth, it’s going to be a very long wait.

What Community Colleges Can Do

What must community colleges do to address these twin crises? In 2019 and early 2020, I participated in a working group convened by Opportunity America that produced The Indispensable Institution: Reimagining Community Colleges. This report contains specific recommendation designed to enable community colleges to achieve their mission “as the nation’s primary provider of job-focused education and training.”

The report advocates for extending community colleges’ workforce development mission and allowing academic credit for all learning that takes place in both the academic and continuing education divisions. This means that short-term certificates attained through continuing education should be “stackable” toward degrees. It argues that all degree programs should include a mix of academic and career-focused courses, that all should include some form of work-based learning, and that all degrees and credentials should have value in the workplace.

To support this approach, the report argues that state funding and accountability systems should be based not on enrollment but on degree or certificate completion and labor market outcomes after graduation. For students who transfer to four-year institutions, the key accountability metric should be four-year completion rates.

At one level, these and other recommendations in the report might seem like common sense, and the report is studded with examples drawn from institutions that are already implementing many of these recommendations. The problem, however, is that such reforms are far from the norm. Assessing transfer programs by four-year degree completion rates, for example, would require a sea-change in current practice. While nearly 80 percent of first-time community college students say their goal is to attain a four-year degree, only 13 percent succeed in doing so within six years.

Currently only 12 percent of U.S. workers have an associate’s degree as their highest postsecondary credential. The working group believes that if all associate’s degrees were redesigned to have immediate value in the labor market, this number could rise dramatically and open new doors to opportunity for many.

Equity and Urgency

One final comment on equity and urgency: it should come as no surprise that Black and Latinx adults and youth are disproportionately represented among both displaced workers and 25-year-olds who do not have four-year degrees. Education and training interventions like those recommended in the report are necessary but insufficient without governmental responses to the underlying causes of the problem.

Low rates of college attainment among young people born into low-wealth families is at least as much a function of huge wealth disparities along racial lines—white families with school-age children have, on average, 100 times the wealth of Black families with children—as of educational factors. If community colleges are given the support they need, they can equip both young people and adults with the skills and credentials to start on a path to economic prosperity. But unless we as a society are willing to tackle the grotesque racial disparities in family wealth, solving these workforce crises will take us only so far.

Related Content

Community Colleges and the Equity Agenda: The Potential of Non-Credit Education

Community Colleges and the Equity Agenda: The Potential of Non-Credit Education This paper addresses the advantages of and challenges to non-credit community college programs for helping low-income students advance. It proposes ways that non-credit and…

A Message to Community Colleges: You Are the Launchpad for Equity

At a meeting of JFF’s Postsecondary State Network, community colleges leaders get a call to be the change agents for achieving equity. The charge: Look for new ways to use data, ask different questions, and…