Centering the People We Serve in Data Collection and Usage

I don’t assume that when we do research or collect and use data that we aren’t centering on the people we serve. On the contrary, as I and others at JFF worked with seven intermediary organizations across the country in the first phase of the Building Equitable Pathways initiative, we saw clear commitments to their respective communities. While different in kind, size, and location, each organization was dedicated to increasing access to the pathways leading to high-wage, in-demand careers for Black and Latinx youth and young people experiencing poverty. This first phase was foundational, focused primarily on the strength and effectiveness of the organization in serving as an intermediary—the “glue” in an ecosystem that binds vision, voice, passion, and people as they do the work.

The second phase of the Building Equitable Pathways initiative is just beginning. This community of practice—up from seven organizations to 14, with many returning from Phase 1—is just as committed to the vision and work as the first. The emphasis for this phase is squarely on systems change through three key areas: policy and advocacy; racial equity; and data and infrastructure. It may be easier to see how people are centered in the first two areas, with “advocacy” and “equity” at least inspiring ideas for what action could look like. “Data and infrastructure,” without context, comes across as a little inert, independent, and agnostic of the people and cultures that make up the communities we intend to serve.

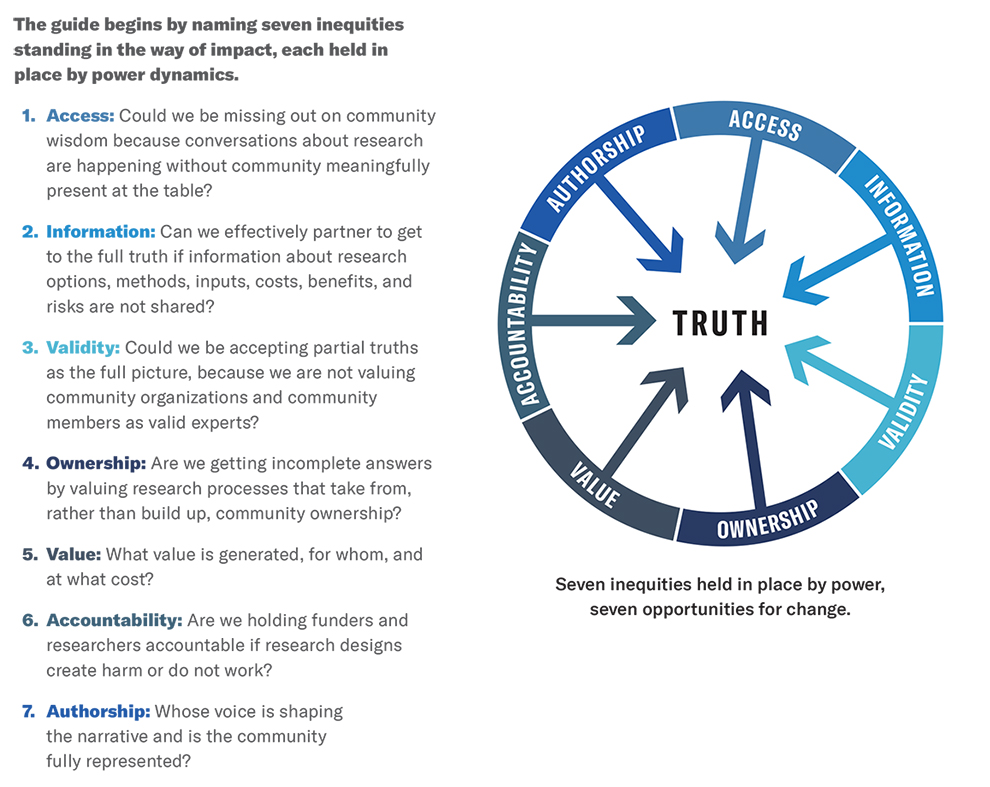

This is why we at JFF are making a commitment to always hold true that data collection and usage will be most effective, as well as respectful, when we keep people at the center. Even further, when possible, we aim to involve the affected communities in that collection and usage, taking a “do with” approach as opposed to a “do for” approach. This approach is supported by a growing number of resources, a sampling of which are offered here.