I live in Shaker Heights, Ohio—a community where children amble down the sidewalks of tree-lined streets, past single-family homes framed by manicured lawns, to neighborhood schools. It is a world away from where I grew up.

Like far too many African American children in the United States, I grew up in poverty. I spent my elementary and middle school years in the Northeast, in an inner-city triple-decker a block from a notorious public housing project that has since been razed. This experience is cruelly common; the poverty rate for African American families is almost three times higher than for white families.

But I had several factors in my favor that many young people from low-income families today do not. Completing college was one of the things that made a difference for me.

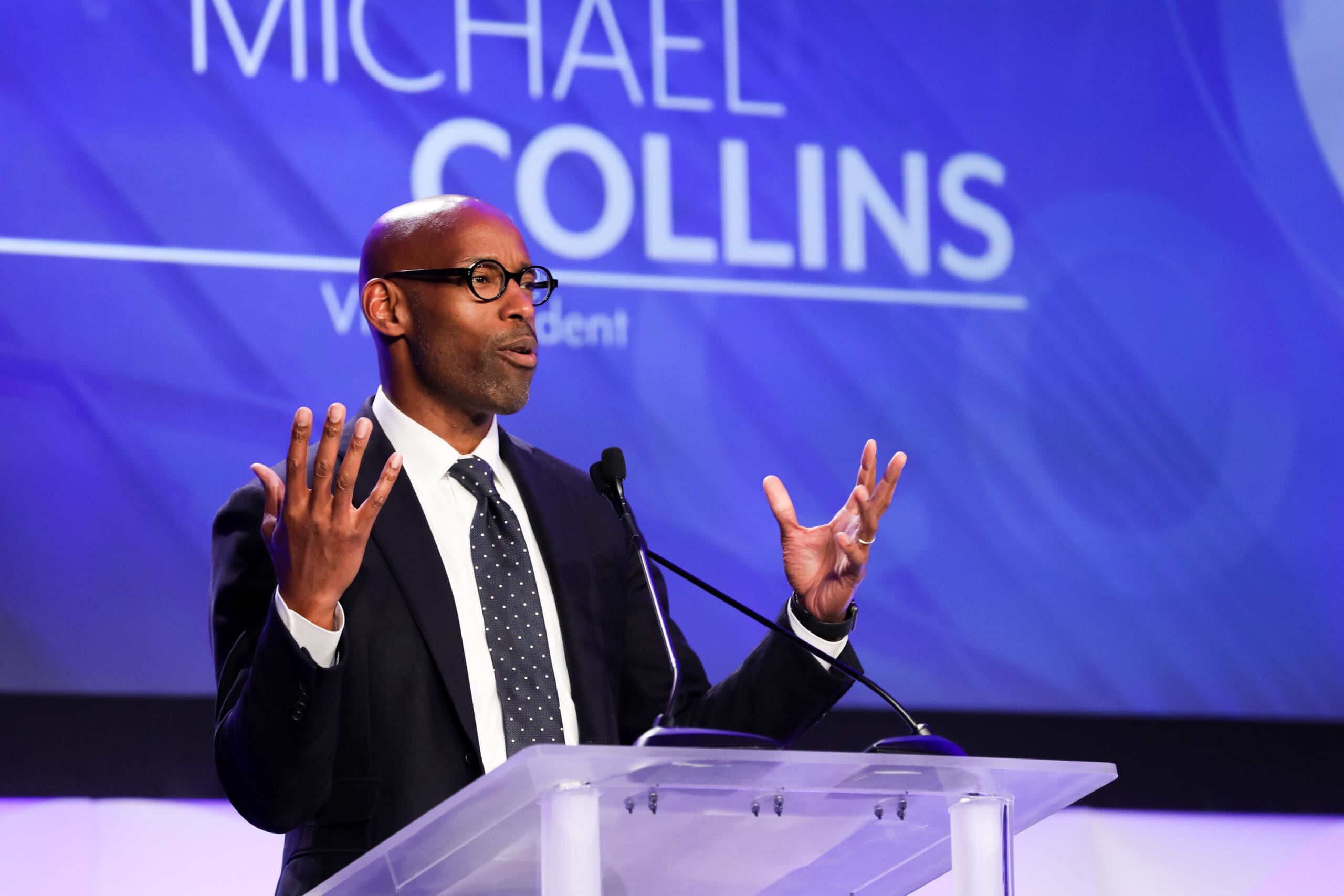

Now, every night, when I tuck my 7-year-old son into bed, I think about childhood friends and millions of others who do not have the high-level skills and college credentials they need to get good jobs, climb the income ladder, and raise their own children in safe, nurturing environments like Shaker Heights. Creating opportunities for the economic advancement of people at the bottom rung of the income ladder is not just a recurring reflection for me. It is a vocation.