Every day, Lisa Lipton goes to work as a clinical director for a mental health services organization, where she counsels people navigating substance use and mental health disorders after incarceration. She has a doctorate in clinical psychology and is a dedicated professional who cares deeply for her clients. Lipton also has a felony conviction and spent four years in federal prison. Although she was released in 2018 and is living a wonderful life, she is reminded every day of her record and the economic barriers that she still faces—a common experience for people who have been involved in the criminal justice system.

Every year, more than 600,000 people like Lipton are released from prison and discover their ability to work, find housing, and get an education is hampered by “collateral consequences,” or legal restrictions governing what people with records can and cannot do.

In the United States, more than 70 million people have a criminal record, and almost all experience the adverse effects of collateral consequences. These outdated and antiquated regulations are demoralizing, punitive, and, in many cases, unnecessary. Lipton’s story demonstrates how when systems—which include workforce, legislative, and social services—create barriers to fair chance pathways for people with records, they exclude real talent from career opportunities and limit equitable economic advancement for a significant part of the workforce.

When Lipton’s probationary periods are finished and she is granted a regular license, she will have spent an estimated $35,000 in fees and expenses related to her probationary licenses. If she had no record of incarceration, she would have paid only $2,000.

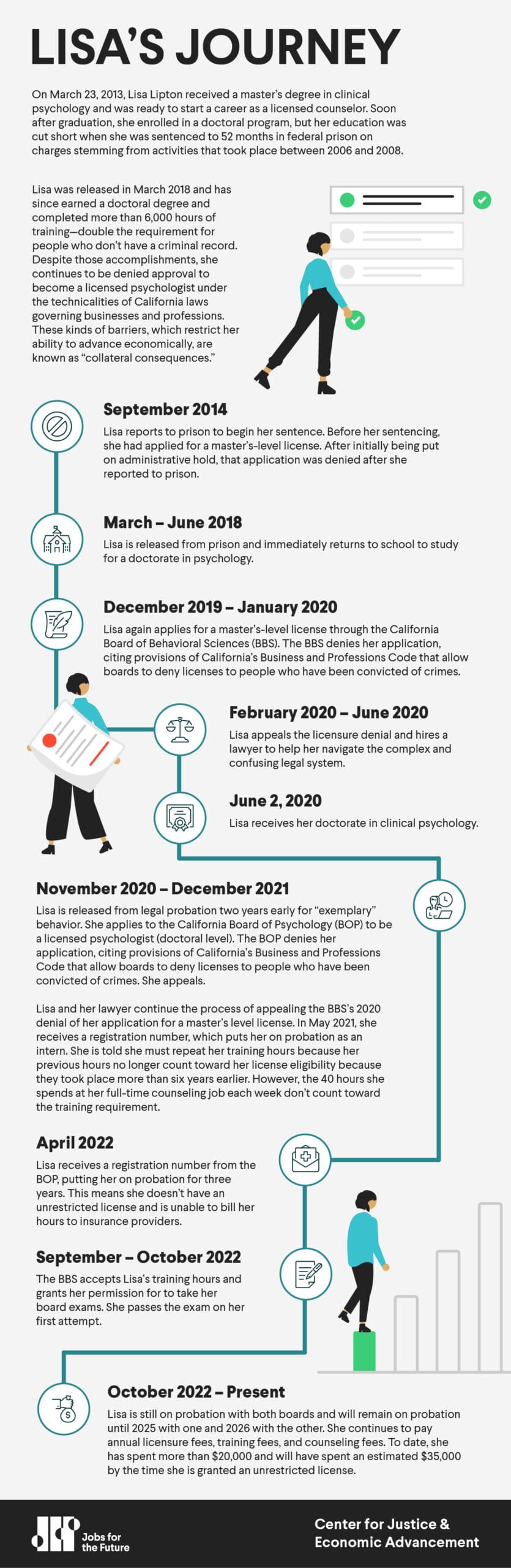

Lipton’s story

In 2014, Lipton was sentenced to 52 months in federal prison. After serving four years, she was released to a federal halfway house in 2018 and reenrolled in the psychology doctoral program she had been studying before her conviction and sentencing. At the same time, she applied for a second time for her master’s-level license with the California Board of Behavioral Science (BBS). Her first application was denied when she disclosed her indictment. Approximately a month later, she was denied that license for the second time.

Because of these denials, Lipton said, “I feel like I am still incarcerated. Everything I do has to be approved as a result of having a felony conviction on my record, no matter how much time has gone by or the qualifications I have.”

Determined to secure licensure, which would push her into a salary bracket aligned with her skill level and education, Lipton filed an appeal, a lengthy process that lasted 27 months. Her case was elevated to the California Attorney General’s office, where in 2021, they ruled in her favor. Lipton was finally granted a probationary master’s-level license from BBS in May 2021, with one key condition: the license remains in probationary status until 2025 and is contingent on her repeating 3,000 hours of an unpaid internship she completed between 2018 and 2020. Lipton is working her full-time job while concurrently completing her internship so that she can have an income.

This grueling process was repeated, including a denial, an appeal, and an additional probationary period, when Lipton graduated with her doctorate and applied for licensing through a different board, the California Board of Psychology (BOP).

Lipton has also incurred significant costs in her effort to get licensed; in addition to her legal fees, she pays $2,500 for the two licenses every year, paid $10,000 for required private psychiatric evaluations for each board, and pays $150 for mandated weekly visits to a therapist. When Lipton’s probationary periods are finished and she is granted a regular license, she will have spent an estimated $35,000 in fees and expenses related to her probationary licenses. If she had no record of incarceration, she would have paid only $2,000.

Nonetheless, Lipton considers herself privileged because she had the support and resources to spend years and money fighting these barriers and working toward her goals. She recognizes this is not the case for most people coming out of prison. For most, the cost and time alone would be prohibitive, causing them never to reach their full economic and social potential—an issue she sees each day working with others who have been incarcerated.

The effect of collateral consequences

More than 40,000 collateral consequences exist for people with records across the United States, but luckily, reform measures are gaining ground. In the past ten years, more than 350 state laws have been passed nationwide to reduce the impact collateral consequences have on people with records. Other significant shifts enacted or planned for this year include:

- California Senate Bill 731, which takes effect in July 2023, will expand automatic expungement for felony convictions that are punishable in state prisons with few restrictions

- An Alameda County, California law bans landlords from discriminating against people with records who are applying for housing

- Full Pell Grant reinstatement, giving people access to education funds during or after incarceration, is scheduled for July 1, 2023

Other proposed national reforms include Ban the Box, which would prevent employers from asking potential employees if they have a criminal record.

However, most reforms are happening at the state level, meaning they only apply to individuals with a state conviction. People like Lipton, convicted of a federal crime, can’t benefit from state expungement efforts; her only hope is a full presidential pardon, which is rare. Gaps in laws and regulations like these create additional barriers and hardships for people with records.

Lipton says she lives in a state of constant worry that she will not meet the various requirements of her probationary licenses, which affects her economic advancement in psychology. Battles to prove her “worthiness” are never-ending, and she fears that when she finally does receive an unrestricted license, she’ll be met with bias from employers who won’t want to hire someone with a record. “I cry. I scream. I fight. And I suffer through this struggle every day,” she says.

As a nation, we must do all we can to reduce the collateral consequences plaguing people with records long after they are released from prison. Policy leaders must pass legislative reforms that normalize fair chance opportunities, promote economic advancement, and remove barriers for people with records. Employers need to implement policies and practices that give people a fair chance at employment and give employers a talented and diverse workforce. As community members, we must explore our own biases about people with records and call upon policymakers to reallocate funds for evidence-based programming that supports reentry and access for returning citizens. We must advance the idea and practice of equitable opportunity, give fair chances to those who have served their time, and discontinue practices that create lifelong sentences after reentry. Our communities will be healthier for it.