February 27, 2025

At a Glance

A literature review of the data and evidence around adult learners (age 25+) in the U.S. postsecondary education system, with particular attention to online settings and Black learners.

Introduction, Methods, and Key Findings

Adult learners make up a significant portion of college and university students in the United States, yet not enough is known about their unique assets and challenges or how postsecondary institutions can best serve them. Since postsecondary degrees and credentials remain a key marker of economic mobility in the United States, understanding the journeys and challenges of adult learners is key to helping adult learners reach their career and economic goals. To fill these knowledge gaps, Jobs for the Future (JFF) conducted a deep review of the data, literature, and evidence around adult learners in the U.S. postsecondary system. Defining adult learners as those age 25 or older, the review also examined two specific subpopulations of interest: online adult learners and Black adult learners (including the cross-section of Black adult learners in online settings). Online settings are increasingly relevant in the current educational landscape, especially for adult learners who are often balancing other life priorities. Postsecondary educational attainment has long been a point of disparity for Black learners in the United States, and Black learners are relatively highly represented among adult learners, providing a key research opportunity aligning with the center’s and JFF’s focus on people facing barriers to advancement.

This review had several key objectives:

- Seek the latest data relevant to adult learners and identify any notable gaps

- Explore the risk factors and barriers associated with adult postsecondary learners and their impact on outcomes

- Identify particular practices shown to be promising in supporting the populations of interest

JFF reviewed literature primarily from the last 10 years, including academic studies and reports from industry organizations, drawn from search engines such as JSTOR, Google Scholar, and the federal Education Resource Information Center. Data on enrollment and outcomes was incorporated primarily from sources under the purview of the Department of Education, including raw and summarized data from various subsidiaries of the National Center for Education Statistics. Additionally, some data was gathered from nonprofit industry sources, such as the National Student Clearinghouse.

In exploring these questions, the review had a number of key findings:

- Adult learners (age 25+) have consistently made up at least one-third of the postsecondary student population for several decades.

- Disaggregated enrollment and outcome data by race and gender for adult learners is lacking.

- Adult learners are more likely to be female, enrolled part-time, and at a public institution.

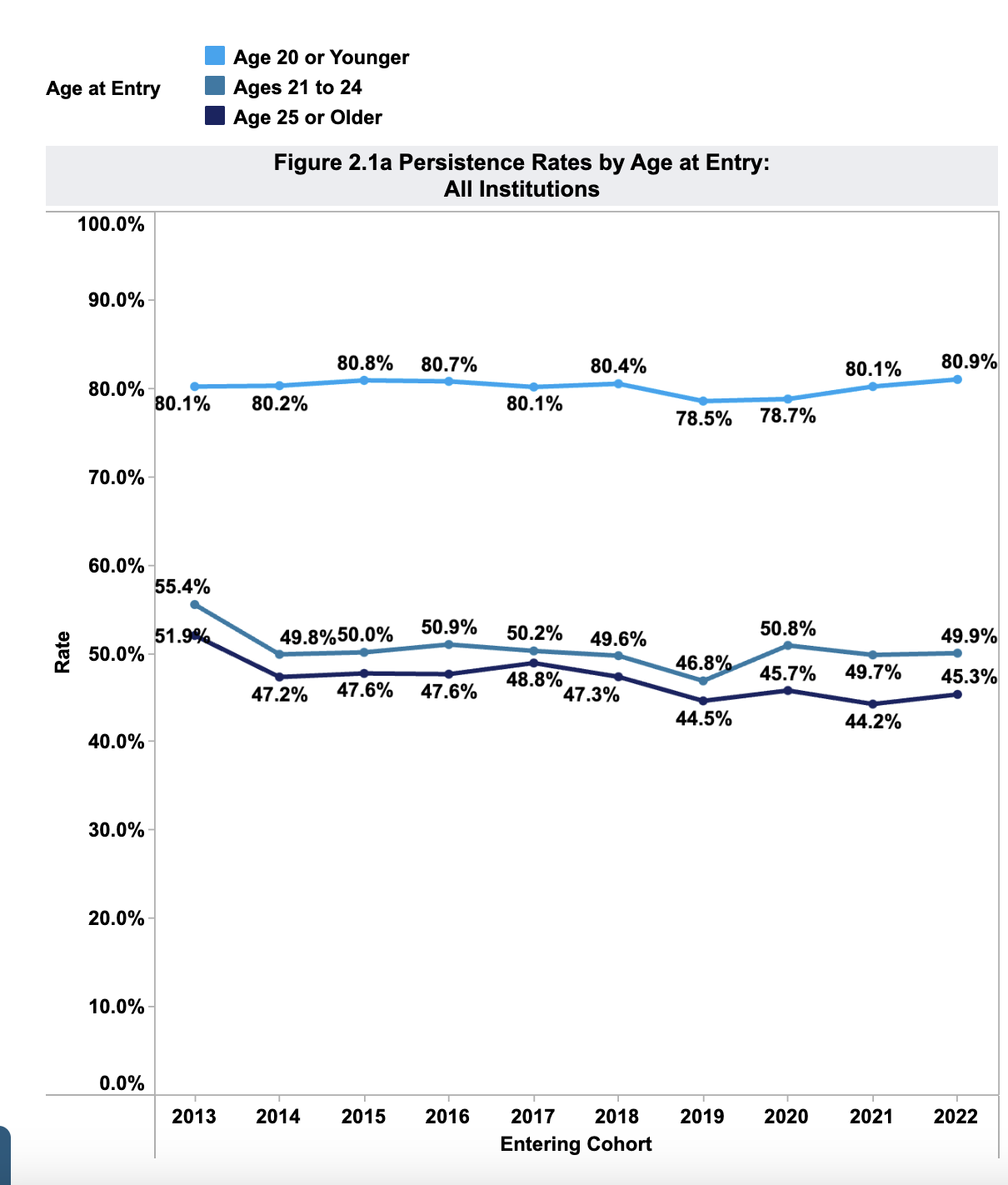

- Year-over-year persistence for students who begin their studies at age 25 or older is 35 percentage points lower than for students beginning at age 20 or younger.

- Evidence shows that many of the key demographic characteristics associated with adult learners, such as parenthood and higher work hours, are negatively associated with postsecondary success.

- Adult learners differ from younger learners, bring unique assets and challenges, and require unique strategies for success. A number of practices show promise for adult learner success.

- There is a limited but developing body of literature exploring how online learning specifically relates to adult learners.

- Formal, high-quality evidence that is specific to Black adult learners, particularly in online settings, is extremely lacking, pointing to areas for further research.

Who Are Adult Learners?

Current Data on Enrollment, Persistence, and Demographics

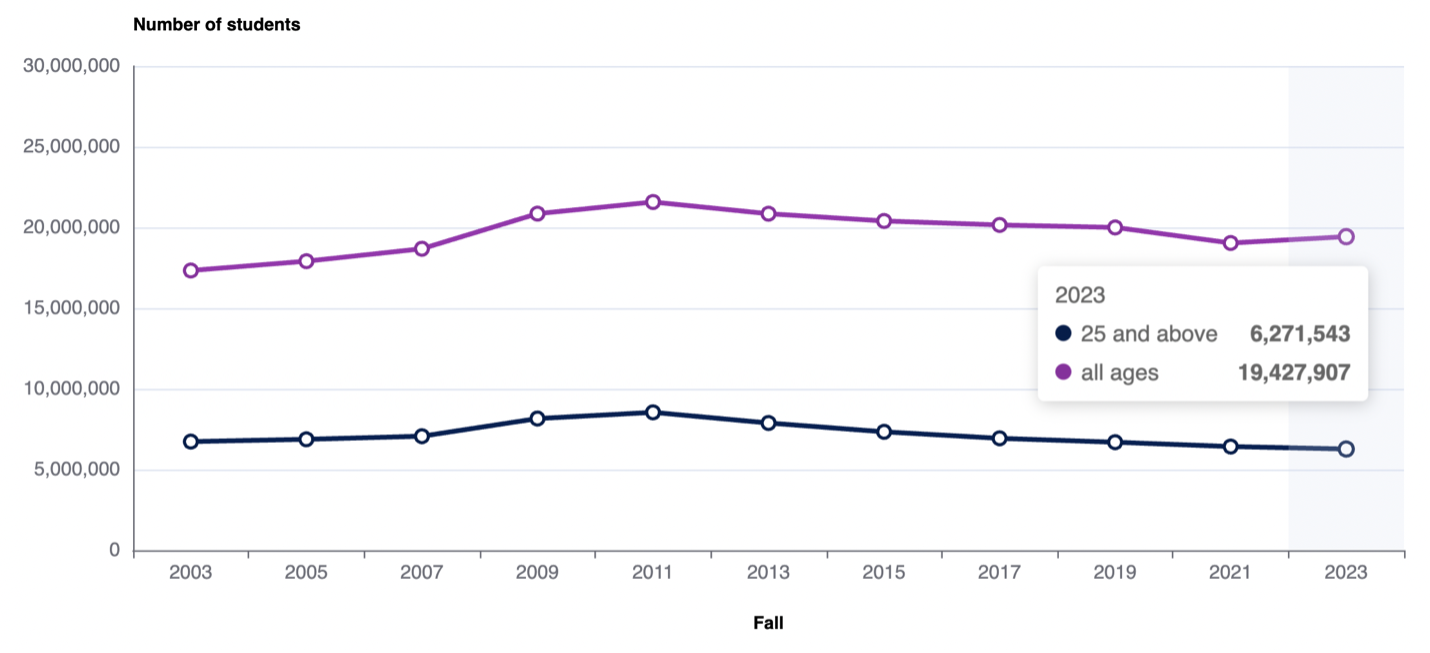

While many think of college students as 18-to-22–year–olds who are right out of high school, adult learners have long been a significant factor in the U.S. postsecondary landscape. Adult college students number about 6.3 million, making up just under one-third of the total 19.4 million postsecondary student population, according to the latest data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). Their data shows that this percentage has declined slightly from its peak in 2011, when there were 8.5 million adult learners (just under 40% of the student population). Through NCES data, we also know that, compared to the general student population, adult learners are far more likely to be enrolled part-time, slightly more likely to be female, and slightly more likely to be at a public institution. And according to data from the National Student Clearinghouse, Black students make up about 15.5% of the adult undergraduate population, compared to just under 11% of the general undergraduate population (as of fall 2023).

College enrollment by total and 25-and-over since 2003. Retrieved from NCES, 2024

College enrollment by total and 25-and-over since 2003. Retrieved from NCES, 2024

Data around online learners is more challenging to gather, particularly by race and age. Through the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), we know that in 2023, approximately 25% of postsecondary students were enrolled in exclusively online education, with an additional 27% enrolled in at least some online courses. Unfortunately, online enrollment data is not disaggregated demographically, leaving some questions as to exactly how adult learners differ in their rates of online enrollment, including by race. One way to gain some insight is to compare institutional enrollment profiles, which in IPEDS include schools’ percentage of learners who are online, above age 25, and of certain races. Doing this, we can see that there is a positive relationship between schools’ percentage of online students and their percentage of adult students. So while precise data around the online enrollment of adult learners remains lacking, available data does support the stance that adult learners are more likely to be online compared to their younger counterparts. Notably, there is no notable relationship between schools’ percentage of online students and their percentage of Black students, indicating that there may not be a significant racial trend in this area.

Caretaker and working-while-enrolled are two key characteristics among adult learners, though this data is not formally collected and reported by most institutions. The best and most recent source of this information is the 2016 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study, which shows that intensity of work increases significantly among students 24 or older, compared to those 18-23. Fewer than 14% of students age 23 or younger worked full-time, but that number rose to 39% among 24-to-29-year-olds and 46% among students 30 or older. As expected, there are also significant differences in parenthood by age. Fewer than 8% of students 23 or younger had a dependent, compared to 33% of 24-to-29-year-olds and more than 60% of students over 30. Regarding age and gender, the study shows that, in general, more female students have a dependent than males (29% compared to 17%), and more Black students had dependents than white students (35% compared to 22%). These gender and race figures are not further broken down by age group.

Finally, it is worth noting that adult learners differ significantly from younger learners in their year-over-year persistence (defined as continuing postsecondary education at any institution). Data from the National Student Clearinghouse shows that students who enter college at age 20 or younger have consistently held persistence rates around 80%, while those who enter college at 25 or older have persistence rates under 50%. As of 2022, the gap was 81% to 46%, showing a significantly greater rate at which adult learners choose to not continue their postsecondary education.

National Student Clearinghouse Research Center

The same trend holds for 6-year graduation rates, with 2023 data from the National Student Clearinghouse showing 64% completion among students starting at 20 or younger, compared to 52% for those older than 24. Once again, persistence and graduation rates by age are not further broken down by race, but the same data shows that, in general, Black students’ persistence rates are approximately 10 percentage points lower than the overall rate. We also know, though, that Black learners are more likely to be adults, who have lower overall persistence. So, currently available data does not address the question of exactly how the persistence rate of Black adult learners compares to white and other non-Black adult learners.

What Makes Adult Learners Unique?

Assets and Challenges

What makes adult learners distinct from their younger counterparts and worth considering separately? Part of the answer relates to their situational characteristics, including things like parenthood and work status, which change how these learners interact with their education. But separately, there is a strong body of literature exploring the dispositional differences in the way adults learn compared to younger students. This concept of adult learning, and the associated methods and practices, is referred to as andragogy and comprises several key principles:

- Need to know: It is important for adults to understand the reason for learning something, and they will engage more deeply when they see the relevance and applicability of the material.

- Self-directed learning: Adults prefer to take on a more active role in guiding their learning, including the planning of goals and assessment of progress.

- Lived experience: Adults draw from their own experiences and use these as the basis for learning; connection to these lived experiences allows for deeper understanding and engagement to the material.

- Readiness: Adults seek to learn things that are immediately relevant and applicable to their lives.

- Orientation: Successful adult learning is oriented around engaging with problems and practical challenges rather than simply taking in content.

- Motivation: Adults respond better to internal motivation (personal goals, career, etc.) than external requirements or motivators.

This framework about internal motivation provides a clear picture of how adult learners may be considered psychologically distinct from younger students. Younger students are still in an exploratory phase of life in which they are developing priorities, goals, and motivations. As a result, younger students tend to need instruction that is more guided and broadly focused, compared to the self-directed style and immediate relevance to which adult learners respond.

One useful framework for considering the challenges faced by adult learners divides barriers into three categories, based on the foundations of adult learner theory: situational, institutional, and dispositional.

- Situational barriers are connected to the material life situation of the learner and may include family obligations, financial constraints, balancing work, and commute/transportation. Our literature review found strong evidence that these barriers significantly impact students’ academic progress:

- Degree completion for students with children lags significantly behind those without children, at 37% vs 60% (for degree completion within 6 years).

- In a 2018 study, researchers found that mothers enrolled in college experienced a significant “time squeeze,” with generally greater fatigue and less happiness.

- Some work can be beneficial to college success, particularly when part-time and/or related to students’ field of study. But evidence shows negative impacts of higher work hours, including on GPA and degree completion.

- Institutional barriers arise from policies and procedures at the learning institution, such as inflexible course schedules, admissions and advising systems that are challenging to navigate, and faculty with limited availability. Key findings here include:

- “Institutional responsiveness” to their learners is shown to be a significant factor in adult learner persistence.

- Dissatisfaction with course options and requirements can be a significant factor in student dropouts among adult learners.

- Accurate academic advising and extended faculty availability have both been identified as key priorities for adult learners transitioning back into postsecondary education.

- Dispositional barriers result from person-specific attitudes, fears, and orientation toward the learning environment. This may include feeling out of place, lack of confidence in abilities, and wavering motivation.

- Fear and doubt are often connected to a lack of confidence after having been away from education, as well as being at a different age and life stage than other students.

- Stress and anxiety have been shown to be significant factors among adult learners, particularly related to academic elements like examinations and presentations.

What Practices Show Promise for Supporting Adult Learners?

Some promising postsecondary practices based on the unique challenges faced by adult learners include the following:

- Transition Programs: Transition programs serve to ease the shift into postsecondary education for adult learners through academic preparation, with many focusing on issues such as academic advising, counseling, and admissions assistance.

- Prior Learning Assessment/Credit: Giving learners academic credit for certain experiences and knowledge gained outside of higher education courses can improve completion rates among adult students as well as increase confidence among students by validating their experiences and connection to academic learning.

- Credit Transfer Pathways: Prioritizing credit transfer pathways is an institutional practice that can greatly ease transitions among adult learners, particularly from community colleges to 4-year institutions. However, this practice requires coordination between institutions to streamline pathways and agree on requisite steps.

- Flexibility for Students: Flexibility in course delivery is a frequently cited priority for many students, as online and evening courses allow learners to balance competing family and career priorities. Beyond just scheduling, recognition of student challenges and related flexibility in both course management and institutional navigations (deadlines, registration holds, etc.) also can have a major impact for adult students.

Black Adult Learners and Online Settings:

What We Know and What Gaps Remain

While evidence for adult learners overall can often be applied regardless of setting or student demographics, it is important to note evidence specifically around online settings, evidence for Black adult learners, and gaps in the literature.

Online settings alleviate many of the situational challenges that adult learners face, but challenges around balancing time and technological competency remain prominent. In online settings, student satisfaction and success are influenced strongly by student-instructor interactions, indicating that an engaging instructor attuned to the specifics of online settings can be highly influential. Course design can also be key; one study found that the structure and layout of online courses were major factors in the degree to which students engaged and succeeded. As online learning continues to grow with technological capabilities, additional evidence will be key to understanding students’ needs and successes, particularly among adult learners, whose specific challenges are often under-discussed in the current literature about online learning.

For Black learners, while there is an extensive body of literature and evidence around traditional learning, relatively little addresses our specific populations of interest: Black adult learners, particularly in online settings. When considering barriers to postsecondary access and success for Black learners more broadly, research points to several factors including financial challenges, discrimination within colleges from faculty and/or students, less access to dual enrollment and AP courses and disproportionate enrollment in remedial courses, and lack of wraparound supports. However, much of the associated literature investigating these challenges provides more insight into traditional learners (on-campus, 18-24-year-olds), and relatively little insight into Black adult learners, particularly those in online settings. Some relevant research does exist; a 2021 study discusses the benefits of “culturally sustaining offerings” for students of color, in which culturally targeted services from institutions can assist Black students by using familiar and relevant methods to increase engagement and feelings of belonging. A multi-year effort funded by the Lumina Foundation aimed at understanding Black adult learners at HBCUs found many overlaps with the existing literature on general adult learners, such as the importance of flexibility and integration of life experiences, with a particular emphasis on the unique experiences of Black adults. JFF’s 2022 call to action around “Achieving Black Economic Equity” also offers recommendations for how postsecondary institutions can better meet the unique needs of Black learners overall.

Going forward, improved evidence is necessary to fully understand how various populations interact with the postsecondary education landscape. On data collection, it remains challenging to access broad, up-to-date data on key subsets of adult learners, including how student age intersects with mode of instruction. Additionally, we know that characteristics like caregiving and work status are significant challenges for postsecondary learners, as well as closely tied to adult learners, but demographic data on these characteristics remains limited and time-delayed, providing challenges in making accurate and timely assessments of these populations. Online learning remains a rapidly growing phenomenon, and additional research is needed to help understand which practices are most effective and how adult learners specifically interact with these settings, including the introduction of new AI technologies. Finally, exploration of the experiences of Black adult learners remains lacking, whether online or not. Black learners remain a key population of interest, as they are relatively over-represented among adult learners, and broader disparities continue to persist in educational and societal outcomes. Through these steps, we can continue to better understand the adult learner landscape and identify opportunities for promoting economic advancement for all.