No Dead Ends: A Policy Agenda Both Sides Can Agree On

This Election Year, Help Us Put an End to Dead Ends at Work, at School, and in Life Jobs for the Future is launching a national campaign calling on candidates to support policies that put…

March 25, 2024

In this brief, Jobs for the Future (JFF) presents our policy recommendations for overhauling the U.S. workforce development and postsecondary education systems—and putting millions more people on pathways to quality jobs.

The U.S. postsecondary education and workforce development systems are in need of transformation. In an ever-evolving economy, where the skills that are required to drive growth are continually changing, workers and employers alike need well-funded, agile, equitable, easily navigable, and effective skills development systems.

At Jobs for the Future (JFF), we’ve embraced an ambitious goal as our North Star: In 10 years, 75 million people facing systemic barriers to advancement will work in quality jobs. We believe an overhaul of the U.S. workforce development and postsecondary education systems is essential to achieving that goal. In this brief, we urge policymakers to pursue 10 legislative and regulatory strategies to help achieve the transformation we envision—and put millions more people on pathways to quality jobs.

Here’s a summary of JFF’s policy recommendations to transform workforce development in the United States:

Before the onset of COVID-19, roughly 75 million people in the United States were unemployed, underemployed, or not working but not counted in official unemployment statistics. The pandemic made the problem worse, as millions of people, especially those in low-paying positions, lost their jobs. While employment has improved significantly since 2021, with unemployment sitting at 3.7% in December 2023, the numbers don’t tell the full story.

More than 6.3 million people in the United States who are counted in the official unemployment rate are still without jobs. Of those, 1.2 million unemployed individuals are experiencing long-term unemployment, meaning they’ve been out of work for 27 weeks or more. Beyond the official unemployment count, an estimated 5.7 million people aren’t included in official unemployment totals because they’ve stopped looking for work, even though they want a job; another 4.1 million people aren’t counted because they’re working part time but would prefer a full-time job; and millions of workers are stalled in low-paying jobs with limited opportunities for advancement. Many of these workers are Black, Latiné, or members of other populations facing systemic barriers to economic advancement.

Meanwhile, U.S. employers continue to experience difficulty hiring workers with the skills they need to fill open jobs. In October 2022, the National Association for Business Economics said that 45% of the employers responding to its most recent Business Conditions Survey reported a shortage of skilled labor. This trend is likely to continue because the skills required for quality jobs will also continue to change as a result of ongoing technological advances and because recent policies—including those in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)—are creating millions of new jobs that need to be filled.

The creation of new jobs combined with a tight labor market should expand the number of career opportunities available to members of populations that have long been excluded from such opportunities. However, transforming the country’s talent pipelines to make them more equitable and inclusive will require significant, targeted investments in workforce development. The U.S. economy and its workers and employers need a well-funded, agile, equitable, easily navigable, and effective skills development system.

Without focused investments in workforce development, the country could miss another opportunity to promote economic advancement for all. In today’s economy, most quality jobs require at least some postsecondary education and training. However, opportunities to acquire the skills and credentials that lead to quality jobs and economic advancement haven’t been equitably accessible to all workers. It’s time to close the longstanding gaps that have limited opportunities for people based on race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.

Congress must significantly increase investments in skills development programs for U.S. workers. And policymakers must enact changes to transform the delivery of education and training.

This country has an array of postsecondary education, skills training, and workforce development programs that provide vital learning and employment services for workers. However, these systems aren’t adequately funded and they aren’t agile enough to fully meet the skill needs of the workforce.

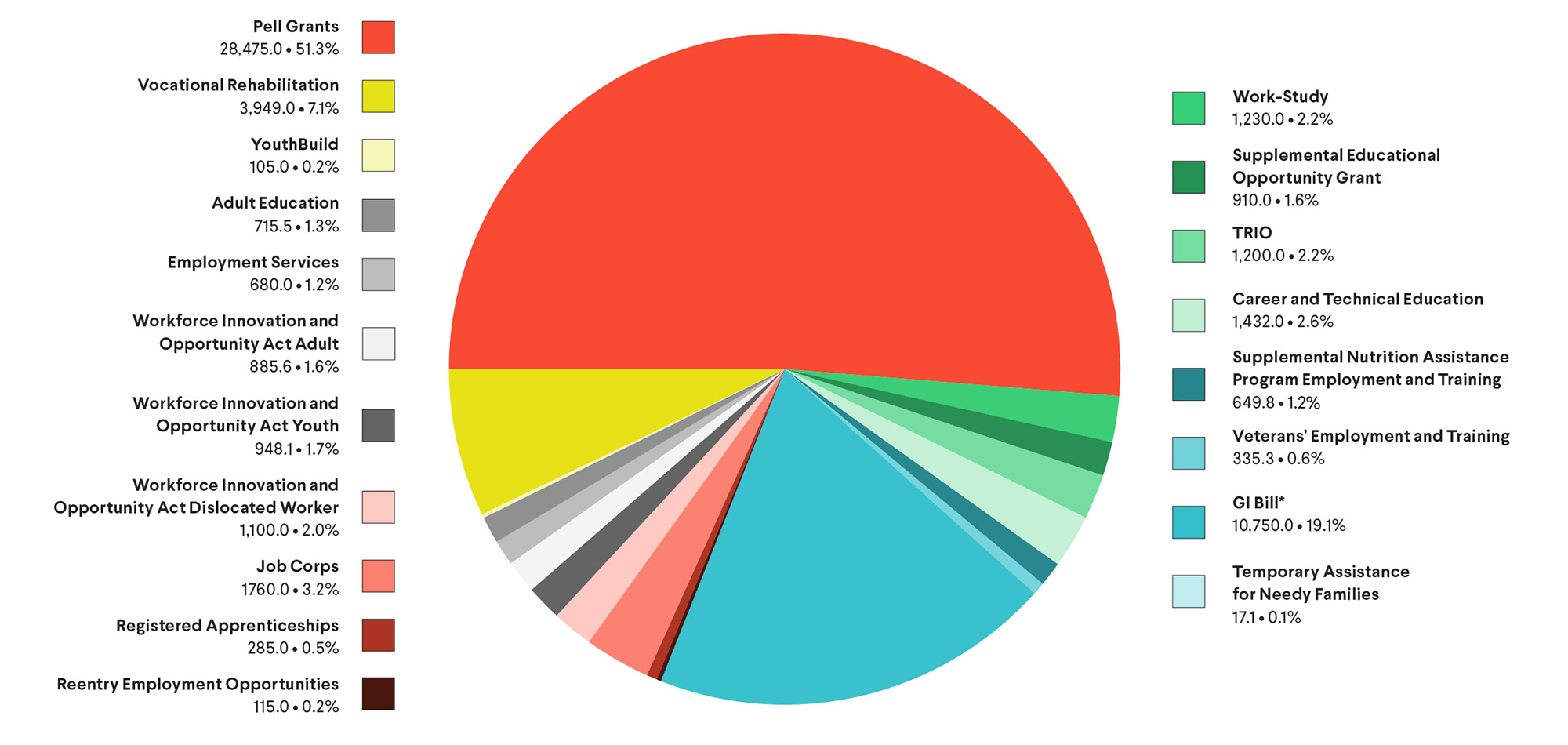

Federal funding for postsecondary education and workforce development efforts totals more than $58 billion annually when taking into account Pell Grants and federal programs that provide education and training assistance for military veterans. The Pell Grant program helps millions of students from low-income backgrounds pay for a postsecondary education, but the program’s inflexible rules make grants unavailable to the growing number of people who want to pursue short-term training programs that lead to industry-recognized credentials. And although the GI Bill and related employment assistance programs are critical to helping former members of the military prepare for new jobs in civilian life, there are no similar comprehensive programs for nonveterans.

Beyond Pell Grants and veterans’ programs, the United States invests only $16 billion annually in initiatives that provide workforce-focused education, employment, and training assistance for the rest of the country’s learners, jobseekers, and workers. This funding is divided among 17 education and workforce development programs, including career and technical education, adult education, and vocational rehabilitation programs, as well as other programs authorized under the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA). In fiscal year 2023, funding for WIOA state formula grants—the primary employment and training assistance resource for adults with low incomes, young people, and dislocated workers—was a scant $3.3 billion for all 50 states.

Current funding levels are not sufficient to provide jobseekers or underemployed workers with the training pathways or meaningful supportive services they need to progress into careers that offer family-sustaining wages. Funding for WIOA’s state grant programs is down about 50% from fiscal year 2000 when factoring in inflation. In fact, investment in workforce development reached its peak in the late 1970s, and to match that level now, policymakers would need to increase annual WIOA state formula allotments to about $35 billion in those programs alone.

The United States would have to spend an additional $80.4 billion on employment and training annually to match the average spending of other Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) member countries (based on percentage of GDP). With millions of people in this country in need of skills development, we must do better.

Workforce vs. Pell Grant Funding: FY23 Federal Funding for Workforce-Related Education and Training Programs

To ensure a future where all workers in this country are able to build the skills they need to land quality jobs and advance economically, and where all employers are able to hire the talent they need, policymakers must invest in U.S. workers at levels that adequately support the economic and skill needs of workers and employers, allow for needed transformation of workforce programs, and bring workforce investments into parity with those of other OECD countries. Just to keep up with inflation, programs under WIOA should be funded at a minimum of $35 billion.

Workers in every sector of the economy are expected to experience employment disruptions as the economy continues to evolve, with a disproportionate impact on individuals who are already underemployed. Millions of people face the need to retool as they prepare to move into new roles and even new industries. The country needs to embark on a new era of research, innovation, and policymaking to enable the sort of economic resilience and advancement opportunities that an equitable economy requires.

Policymakers must support modernization of the U.S. workforce development system by aligning disconnected federal employment and training programs; streamlining infrastructure toward a regional service delivery model with updated governance; redirecting fragmented funding streams through a single workforce delivery system that is comprehensive, agile, and capable of meeting the skills needs of regional economies; and augmenting and improving service delivery through IT infrastructure updates and the use of new technologies and improved data systems. This comprehensive workforce development initiative must also include efforts to transform the delivery of education and training in ways that accelerate learning so people spend less time in the classroom and provide credit for prior learning regardless of where it occurs (see Section IV). JFF urges policymakers to take the following actions.

AT THE FEDERAL LEVEL:

Establish an Office of Workforce Innovation in the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) to build an advanced research capacity and transform the workforce development system. Modeled on DARPA—the U.S. Department of Defense’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency—the new DOL agency could work with innovators within and outside of government to make investments in breakthrough technologies and other strategies that improve the way workforce development services, including career navigation and skills training, are provided and financed in the United States.

Establish a Data and Technology Transformation Fund to do the following: support the above-described federal activities; fund direct work with employers and national employer associations on multistate training and credentialing efforts; give stakeholders incentives to engage in cross-state and multi-state initiatives such as the Workforce Data Quality Initiative or the Statewide Longitudinal Data Systems Grant Program; and provide funding to states and regional workforce systems to modernize state and regional workforce data and technology efforts. This includes the integration of technology into career navigation and training services at American Job Centers and related providers.

Fully align disconnected employment and training activities and funding streams at the federal, state, and regional levels—including employment and training activities under WIOA, the U.S. Employment Service, the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development programs—through a single, streamlined workforce development system with common intake processes, standards for determining eligibility, and performance metrics. The federal government should also form an inter-agency workgroup tasked with identifying recommendations for developing such an aligned system and for eliminating the “benefits cliff,” where people who receive public benefits risk abruptly losing those benefits when they get wage increases.

AT STATE AND REGIONAL LEVELS:

The United States lacks a comprehensive career navigation system that can help learners, parents, jobseekers, and workers make well-informed choices about education and career paths. The workforce system established under WIOA provides career navigation services to youth and adults who are seeking jobs or making career changes through the WIOA system, but these services are in need of modernization and are currently restricted to individuals participating in WIOA programming. JFF urges policymakers to do the following:

The United States must invest in the skills of its workers and make changes in the ways education and training are provided to meet the needs of all learners, jobseekers, workers, and employers. JFF urges policymakers to do the following:

The United States must invest in the skills of its workers and make changes in the ways education and training are provided to meet the needs of all learners, jobseekers, workers, and employers. JFF urges policymakers to do the following.

In today’s economy, we’re seeing a significant increase in demand for short-term occupational skills training. People who are looking to quickly reenter the labor market and many secondary and postsecondary students are seeking learning opportunities that help them develop the skills they need to land quality jobs. That means it’s essential to have reliable ways to assess the quality of both short- and long-term education and training programs—to provide accurate information to consumers and to lawmakers and regulators, so they can make informed public funding decisions. Policymakers can do the following to better ensure program quality.

Employer engagement and mobilization are key to the success of workforce development efforts. Employers must be involved in the design and implementation of new workforce development programs to ensure that they offer workers opportunities to acquire the skills and credentials that are in demand in regional economies. And to better serve jobseekers and workers, employers should also implement new recruiting and talent management practices, such as skills-based approaches to hiring and advancement. To encourage these behaviors and increase employer investments in their own frontline workers, policymakers can take the following actions.

To ensure that members of populations facing barriers to employment—including opportunity youth, individuals with disabilities, people of color, workers with low incomes, people with criminal records, and people who are learning English—have opportunities to acquire the skills and credentials needed for quality jobs, policymakers must craft measures designed to provide the following:

In December 2023, the U.S. youth unemployment rate was 8%, compared to 3.7% for the general population. It’s estimated that there are nearly 4.7 million young people ages 16 to 24 in this country who are both out of school and unemployed—the population that many organizations and policymakers refer to as “opportunity youth”—and more than one-third of opportunity youth are living in poverty.

There’s an urgent need for programs that can help the members of this population build skills and gain work experience. Unfortunately, funding for programs designed to serve them has declined precipitously since its peak in the late 1970s. Today, the primary federal program serving opportunity youth is the WIOA youth program, which allocates funding to states and local areas based on a formula. In Fiscal Year 2023, funding for WIOA youth totaled only $948 million, and the programs it supported served just 127,708 young people.

To address the needs of this population, policymakers should take the following actions.

Now is the time to transform this country’s workforce development system. To do this, policymakers must invest and make changes in the country’s education, workforce development, and economic development systems that are necessary to ensure that the U.S. economy remains strong and that workers of all backgrounds have the skills they need to succeed.

By increasing resources for skills development, modernizing career navigation and training services, providing necessary transition assistance for learners and workers, involving employers in the design and implementation of workforce development programs, and ensuring that individuals with barriers to employment have access to high-quality services, we will make sure that all individuals, including members of populations that have long been underserved by existing systems, can achieve their full potential.

JFF urges leaders in Congress and the Biden administration to take action and create a workforce system that works.

Mary Gardner Clagett, Senior Director for Policy, JFF

David Bradley, Senior Director for Workforce Policy, JFF

Susannah Rodrigue, Senior Manager for Policy, JFF

This Election Year, Help Us Put an End to Dead Ends at Work, at School, and in Life Jobs for the Future is launching a national campaign calling on candidates to support policies that put…

Drawing from our experience aspolicy lead for multiple nationally recognized community college completioninitiatives over the past decade, JFF has developed a suite of policy andadvocacy services to help Student Success Centers and their partners at…

The Education and Workforce Committee’s bipartisan development of “A Stronger Workforce for America Act” holds great potential for the country’s learners and workers, but increased funding for the nation’s workforce system is needed to fulfill…