Redesigning Training Programs for the COVID-19 Era and Beyond

October 14, 2020

At a Glance

Training and education will be key to helping displaced workers find stable jobs in the post-pandemic recovery, but programs need to be reimagined with equity at the forefront to ensure that they benefit everyone equally.

Black, Latinx, and low-income workers have been hardest hit by this pandemic-driven recession, and they will likely have the hardest time finding good jobs once the threat of COVID-19 has eased.

The stark reality is that many of the jobs that were lost won’t be coming back. That means displaced workers will need training in order to find new jobs and get on a path to economic mobility.

Even prior to the pandemic, it was clear that education and training programs did not serve all populations equally well, and the shift to remote program delivery has added new barriers to access and success for low-income and underrepresented populations.

Education and training programs can play an important role in driving a more equitable recovery, but not without adaptation and innovation.

The inequities brought to light by the current unemployment statistics are impossible to ignore. According to the Strada Education Network, as of June 10, Black and Latinx workers had lost their jobs at a rate that was more than 50 percent higher than that of white workers, and half of all workers Strada surveyed said they were concerned about losing their jobs. And a recent Pew Research Center report reveals that COVID-19 has primarily impacted workers who are women, Hispanic, immigrants, between the ages of 16 to 24, and without any college education. Before the pandemic, workers of color were already overrepresented in low-wage work. Now, as some sectors of the economy slowly reopen, we are seeing that COVID-19 has accelerated the pace at which jobs are being automated, and this automation-driven job loss is more common in occupations held by minority workers. In addition, we already see white workers are getting hired back at twice the rate of Black workers. Without deliberate intervention, recovery from COVID could end up widening existing income and wealth gaps.

It’s clear that training must play a key role in addressing this problem. The demand for upskilling is there: At the end of August, Strada reported that the share of Americans who said they planned to enroll in an education program within six months had stood at about 20 percent since May, and 62 percent of those with enrollment plans had consistently expressed a preference for nondegree and skills training programs.

But not everyone has equal access to training opportunities, and not all training opportunities deliver equitable outcomes. These inequities have been exposed and exacerbated by the ongoing health care and economic crises. For example, the magnitude of the digital divide has become glaringly apparent as many training programs have had to shift to remote learning models during the pandemic.

Nonetheless, because we’re in a moment of change and transition, we have an opportunity to make training programs more equitable. We can adapt existing programs and design new ones to better serve the immediate and long-term needs of workers—programs that not only teach people the skills they need to find new jobs quickly, but also provide them with lifelong learning opportunities.

In this brief, JFF explores what training providers can do to adapt their programming in ways that put the country on a path to an equitable economic recovery. JFF conducted research to explore what education and training providers can do to design programs that emphasize equity and better serve individuals who face the most barriers to employment.

In interviews with representatives of community colleges and community-based organizations (CBO), and with JFF employees who work directly with workforce boards and training providers, we focused on understanding how the shift to remote delivery has affected training programs—both positively and negatively. We asked whether online learning enabled them to do things they previously could not do and encouraged them to discuss challenges they’re facing and successes they’ve enjoyed.

One theme throughout our interviews was that the abrupt shift in program delivery has provided a unique challenge to make changes that we have long known to matter for student success – such as creating more flexible learning options and focusing on transferrable skills. Based on what we learned, we came up with recommendations for ways in which training providers can reimagine and redesign their programs with an equity lens. Importantly, these recommendations will remain relevant beyond the current health crisis.

Our recommendations are based on these two cross-cutting design principles:

- Keep equity at the forefront

- Remain flexible and open to change

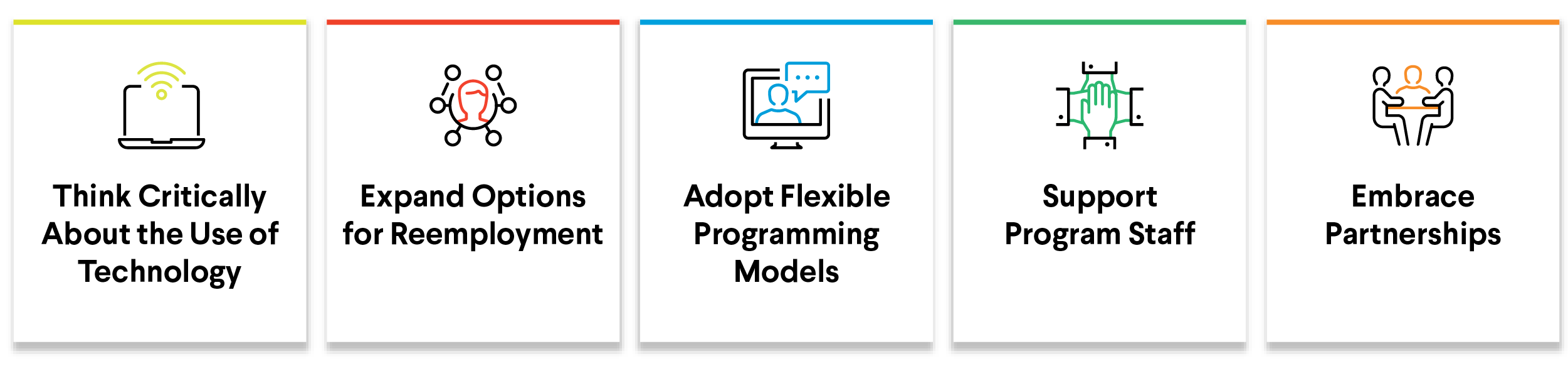

Those two principles in turn inform five design considerations that we believe training providers should take into account as they adapt and revamp their programming in the COVID era:

- Think critically about the use of technology

- Expand options for re-employment

- Adopt flexible programming models

- Support program staff

- Embrace partnerships

In addition to those design principles and considerations, there’s another factor that we believe training providers should keep in mind, especially in this time of crisis: the impact of trauma that learners, workers, and program employees have experienced in their lives.

Our two guiding principles for training providers to embrace as they adapt their programs in response to the impacts of COVID-19 serve as the overarching guide for the five more detailed design considerations we put forth later. They should be front and center throughout all phases of design, implementation, and evaluation of programs.

Principle 1: Keep Equity at the Forefront

Why is this important?

The pandemic and the recession are disproportionately impacting people from underrepresented communities. The decisions that training providers make as they adapt to the current reality will determine who can access and complete skills training—and those decisions will ultimately determine who will be able to find gainful, long-term employment during the post-pandemic recovery. If we want to come out of this crisis with a more equitable society, training programs must be intentional about adopting practices and policies that support those who have been most impacted by the pandemic.

What this looks like.

There are a number of ways that training providers are infusing an equity lens into program adaptation. Some are inviting program participants to participate in the design process. Others are adapting recruitment and outreach materials so that they appeal to a more diverse audience and integrating a Universal Design for Learning approach to training delivery. It’s an ongoing process—providers must regularly assess how their adaptations are affecting different populations and make changes as needed.

Principle 2: Remain Flexible and Open to Change

Why is this important?

Providers must always be prepared to adapt and reimagine their programs to better align their offerings with the needs of learners and the shifting dynamics of their local labor markets.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, U.S. education and training systems were known for being slow to change course. Policy and bureaucracy made it difficult to adapt curricula to changes in labor market or integrate new ways of engaging students and helping them learn. Employment-oriented training programs often focused on a narrow set of occupations, and many policies had unintended and disproportionately negative impacts on learners and workers of color.

As the pandemic has brought programs to a halt entirely or limited providers’ ability to move work forward, practitioners have had to approach their work with new flexibility, in terms of both program delivery and labor market alignment. Even if we’re one day able to return to business as usual, the most successful education and training programs will be those that are able to align with local labor market needs and continually adapt to ever-changing economic realities.

What this looks like.

The pandemic has made it clear that when necessary, training programs can move quickly to make changes. They can move administrative processes online, redesign assessments, and create new support structures for students. In part, the crisis forced a shift in mindset from “this is how we always done this” to “this is what our learners need right now.” Even outside of a crisis, training programs should regularly be assessing whether their programs and policies are actually working for learners. The most forward-thinking programs have been able to view the shift to remote instruction as an opportunity to think about long-term transformation across all facets of their work, including organizational structure and capacity, policies and procedures, design of training and curriculum, and creation and expansion of partnerships.

Through our research, we identified five design considerations that training providers may want to keep in mind as they adapt, and ideally improve, their programs in response to the realities of the COVID-19 pandemic. A range of practitioners and programs, including community colleges, workforce boards, and CBOs, have adopted promising practices that reflect and embody these design considerations, which in turn are shaped by the two aforementioned guiding principles.

Here are more detailed discussions of each of the design considerations, with examples of ways in which training providers have incorporated them in newly reimagined programs.

As the demand for training increases, it is critical that programs be designed with equity as a guiding principle to ensure that the people who have suffered the most during the current health care and economic crises get the support they need and are not left behind when the recovery begins.

However efforts to redesign and overhaul training programs must do more than respond to the current reality of our nation and of the world. This is more than just a moment—it’s the start of a long journey. The goal isn’t to go back to the education and training systems that existing before the pandemic–it’s to build something better than what existed previously. Because the challenges we’re facing and the potential solutions to those challenges are intersectional in nature, the advice and recommendations in this brief are designed to be versatile—developed not only for training providers, but also for all stakeholders working toward a more equitable future.

The design principles and considerations presented in this brief are grounded in the current reality, but at the same time, they allow room for innovation that leads to unconventional and bold changes. Equity, flexibility, and adaptability are critical considerations for not just training programs, but also as we build systems that will help us move forward on this long journey

JFF recognizes that our recommendations are bound to change as the world continues to wrestle with new and evolving crises, so we welcome all and any feedback, questions, and stories.

Methodology

JFF conducted research for this project primarily in August 2020.

We interviewed representatives of 13 community colleges, CBOs, and workforce development boards. We also spoke with eight fellow JFF employees who work directly with community colleges, CBOs, and other training providers. In addition, we included comments from community college faculty members who participated in an April 20, 2020, Achieving the Dream virtual town hall on the steps schools were taking to support students during the shift to remote learning at the onset of the pandemic.

The representatives of community colleges that we spoke with were campus leaders in academic affairs, career services, student services, accreditation and planning, and workforce development. Interviewees from CBOs and workforce development boards had titles such as CEO, chief innovations officer, and director of gateway initiatives.

The interviewees represented a geographically diverse collection of organizations based in 12 states on the East and West Coasts, and in the South and Midwest. The colleges ranged from single-campus institutions to a statewide system with 14 main campuses, and their undergraduate populations ranged from 2,000 to 75,000.